Today I've got a very sad poem sequence, also from Kikusha. Kikusha's Chinese poetry is very hard for me, so this is by no means perfect. I hope it at least give a hint of the remarkable range of this talented, perpetually questing woman.

(一)

二十年来忘累機

風雲誘処促単衣

環郷松菊東籬遍

禄髪為霜去不帰

(二)

幾年逃世片心微

孤錫帰来叩旧扉

愁殺荒涼深竹色

此君今独立依依

うきわれを照せ昔の秋の月

Headnote: Already more than 20 years have passed since I became a widow, and I have been traveling from east to west. In the autumn of 1798 I returned home, and happened to visit my father-in-law's house. I wrote these two verses to express some of my feelings then.

I.

Twenty years have passed and I have forgotten many moments

Since the spirit of travel beckoned me and I set out with just a single garment.

Going back to my hometown, pines and chrysanthemums are everywhere east of the fence

My black hair turned to frost before I returned from far away.

II.

I grew tired of avoiding the world after countless years,

Returning home with my solitary traveler's staff I knocked on my old door.

I was overwhelmed by sadness, and a deep sorrow

Where he had been now flourishes lonely longing.

shine your light on me,

as I mourn for a distant past --

autumn moon

Teaching and reading classical Japanese literature, especially haiku

Sunday, November 9, 2014

Sunday, November 2, 2014

Kikusha, for All Saints / Day of the Dead

Kikusha wrote some very interesting works: poems in Chinese that were followed with a hokku, in the style of Manyôshû chôka (long courtly-style verse) that were concluded with hanka ("envoy" verses).

I am not sure this is right. I've followed the interpretation in Isobe Masaru's 磯辺勝 Edo haiga kikō: Buson no hanami, Issa no shōgatsu 江戶俳画紀行 - 蕪村の花見、一茶の正月 (央公論新社, 2008).

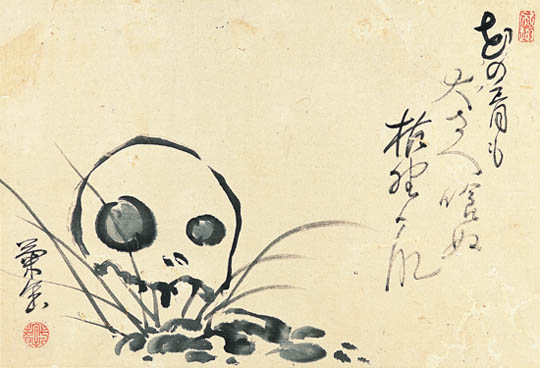

題髑髏図

借問誰家子

紅顔墜露前

懐余這箇物

風動薄茅辺

花の骨ながら犬さへ喰へぬかな

Topic: Skull Picture

May I ask, what family’s child was this?

Still young, fallen frail as the dew.

I ponder on these things that remain

Wayside weeds and grasses, blown by the wind.

withered miscanthus may be called “flower bones”

but they are not

for dogs to gnaw

The picture comes from the Kikusha Commemoration Society's site.

借問誰家子

紅顔墜露前

懐余這箇物

風動薄茅辺

花の骨ながら犬さへ喰へぬかな

Topic: Skull Picture

May I ask, what family’s child was this?

Still young, fallen frail as the dew.

I ponder on these things that remain

Wayside weeds and grasses, blown by the wind.

withered miscanthus may be called “flower bones”

but they are not

for dogs to gnaw

The picture comes from the Kikusha Commemoration Society's site.

Saturday, October 25, 2014

The Courtesan Kasen

Here are some hokku by Kasen 哥川 (ca. 1716-1776). I'm sure I've read some of these wrong, but here they are anyway. Courtesans led tragic, frequently brutal lives. These verses, however, are very evocative and romantic.

upon awakening

I tuned my koto

to the sound of spring rain

目覚ましに琴調べけり春の雨

envious that

snow does not gather on its branches

the plum tree itself blossoms

うらやましつもらぬ雪の梅もさき

without tying back

her beautiful hair --

willow tree

美しいかみもゆはずに柳かな

morning glory --

I too, await someone,

taking a flower for my companion

夕顔やわれも人まつ花のとも

when tying back my hair

I gaze outside --

scattered poppy blossoms

かみゆふて見れば散りたりけしの花

airing out clothes --

a cherished letter

falls from her sleeve

虫干しや恋しきふみのたもとより

These are in Nakajima Michiko's 中島道子 Yûjo Kasen: Echizen Mikuni-minato no haijin 遊女哥川: 越前三国湊の俳人 (渓声出版 [1985]). It's a biographical novel. Sometimes it's so sad/horrific I find it hard to read; it's full of useful information, though.

upon awakening

I tuned my koto

to the sound of spring rain

目覚ましに琴調べけり春の雨

envious that

snow does not gather on its branches

the plum tree itself blossoms

うらやましつもらぬ雪の梅もさき

without tying back

her beautiful hair --

willow tree

美しいかみもゆはずに柳かな

morning glory --

I too, await someone,

taking a flower for my companion

夕顔やわれも人まつ花のとも

when tying back my hair

I gaze outside --

scattered poppy blossoms

かみゆふて見れば散りたりけしの花

airing out clothes --

a cherished letter

falls from her sleeve

虫干しや恋しきふみのたもとより

These are in Nakajima Michiko's 中島道子 Yûjo Kasen: Echizen Mikuni-minato no haijin 遊女哥川: 越前三国湊の俳人 (渓声出版 [1985]). It's a biographical novel. Sometimes it's so sad/horrific I find it hard to read; it's full of useful information, though.

Friday, September 26, 2014

Sanzôshi 7 - Twilight of Autumn

Some more favorite verses from Akazôshi. It's way too early in the year for aki no kure, but I suppose it's always twilight on the earth, somewhere.

people’s voices —

coming home on this road

twilight of autumn

hito koe ya kono michi kaeru aki no kure

人声やこの道かへる秋の暮

on this road

no one else travels

twilight of autumn

kono michi ya yuku hito nashi ni aki no kure

この道や行く人なしに秋の暮

About this verse: Someone asked, “Which is better?” Later, he decided on “no one else travels,” and published it under the topic “Inner Thoughts 所思.”

Tuesday, September 23, 2014

Sanzôshi 6 - Six Hokku

A set of hokku from Akazôshi. Dohô lists them together as verses that Bashô revised. They're not autumn verses, but I post them in honor of the equinox and first day of autumn, as Bashô was a rather autumn/winter kind of person.

banana tree in a storm —

a night of listening

to rain in a bucket

bashô nowaki tarai ni ame o kiku yo kana

芭蕉野分盥に雨を聞く夜かな

see you later

banana tree in a storm —

a night of listening

to rain in a bucket

bashô nowaki tarai ni ame o kiku yo kana

芭蕉野分盥に雨を聞く夜かな

see you later

I’ll be snow-viewing

until I’m rolling in it

izasaraba yukimi ni korobu tokoro made

いざさらば雪見に転ぶ所まで

wintry winds —

I am just like

Chikusai

kogarashi no mi wa Chikusai ni nitaru kana

木がらしの身は竹斎に似たる哉

coming upon them, on a mountain road

how lovely!

wild violets

yamaji kite nani yara yukashi sumire gusa

山路来て何やらゆかしすみれ草

a family, all of them

with canes and white hair

visting the cemetery

ie wa mina tsue ni shiraga no haka mairi

家はみな杖に白髪の墓参り

Buddha’s birthday —

wrinkled hands pressed together

sound of rosary beads

Kanbutsu ya shiwade awasuru juzu no oto

灌仏や皺手合する数珠の音

Originally the “storm” verse had two excess morae, “nowaki shite (as it storms).” Originally the “snow-viewing” verse started with “iza yukan (so, let’s go).” “Wintry winds” originally had excess morae, “kyôku kogarashi (mad verse wintry winds).” “Wild violets” originally had “nan to naku nani yara yukashi (why, how lovely!).” “A family, all of them” originally had “ikka mina (the whole family).” “Buddha’s birthday” also originally sounded like “nehan e ya (nirvana painting);” did he revise it later? Surely there are others of this kind. All of them show our Teacher’s changes of heart, and should be appreciated.

Wednesday, September 17, 2014

Sanzôshi 5 - Lingering Dreams

This Akazôshi passage discusses one of my favorite Bashô verses, so here it is:

Though a dim light shown from the late-month moon at the dawn of the twentieth day, the base of the mountains was deep in darkness; even the pony’s hooves clomped clumsily and several times I thought I’d fall off. In that way we passed countless miles, with no birdsong audible yet. I thought of Du Mu’s lingering dream in “Early Travel,” and woke up at Sayo-no-nakayama:

dreams linger while sleeping on horseback

the moon, in the distance

a tea-fire’s smoke

uma ni nete zanmu tsuki tôshi cha no keburi

馬に寝て残夢月と遠し茶の煙

About this verse: The headnote uses the words of an ancient poet to illuminate a scene. Originally, it read: “on horseback, lingering dreams as I’d like to sleep / the moon in the distance / a tea-fire’s smoke 馬上眠からんとして残夢残月茶の煙 bajô nemukaran toshite zanmu tsuki” and at one point the first five morae were edited to read, “sleeping on horseback 馬に寝て uma ni nete;” after that, the rhythm did not seem right, so it was amended to “the moon in the distance / a tea-fire’s smoke 月遠し茶の煙 tsuki tôshi cha no keburi.”

| Saigyô verse memorial at Saya-no-yamanaka Park | www.city.kakegawa.shizuoka.jp |

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

Sanzôshi 4 - The Red Notebook 2 赤冊子

More Akazôshi. This part includes some of Bashô's famous statements on the balance of high and low culture in haikai, and the importance of objective observation.

One of his teachings was, “Awaken to the things of elite culture, but return to the things of the everyday life.” He said, “Always strive to awaken to aesthetic authenticity; at the same time, you must return to the haikai of the present moment.”

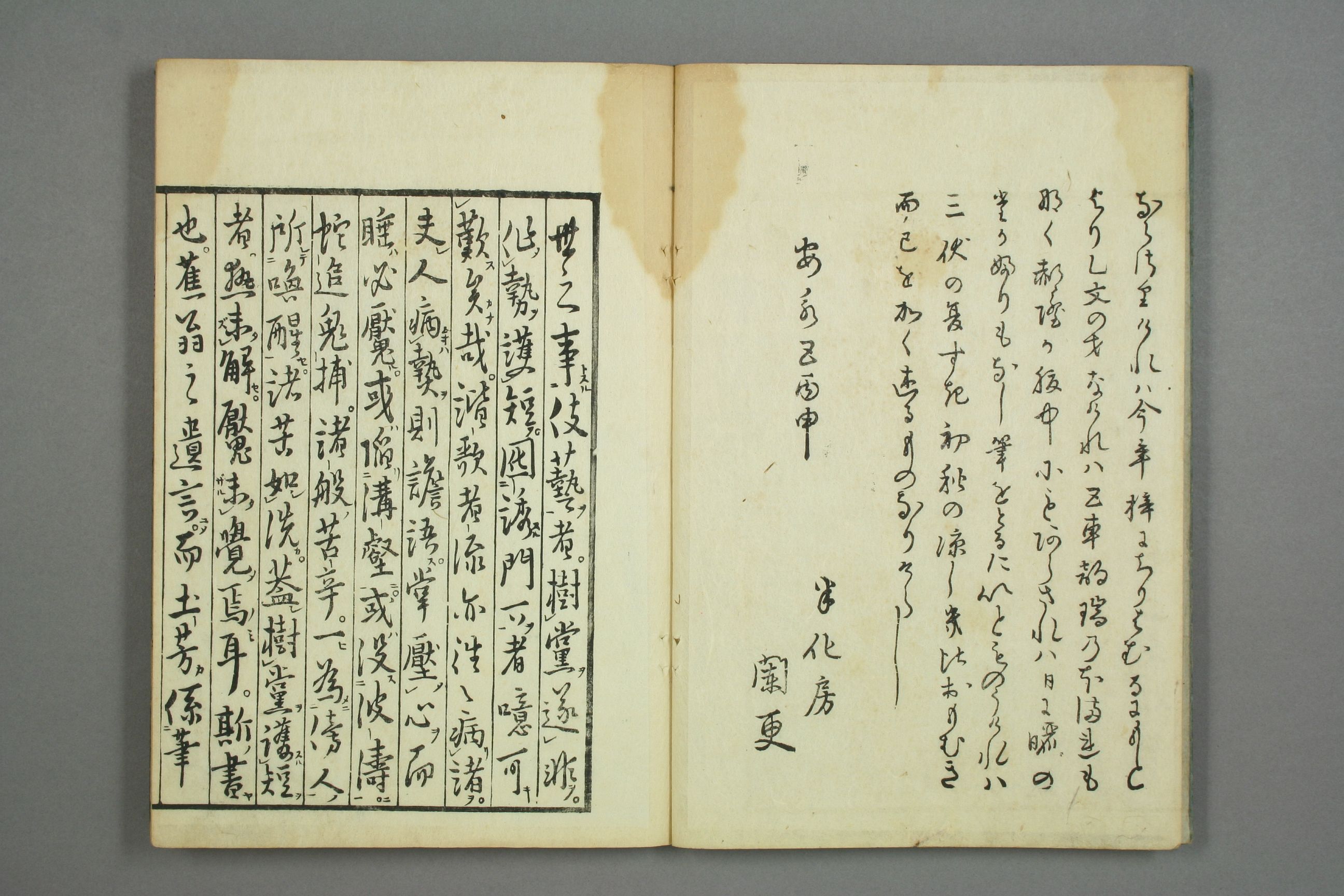

|

| Sanzôshi, Waseda Library |

Because poets who always concentrate on poetic elegance unify the object about which they write with the emotion that they feel and fix it in the form of a verse, the theme they take up emerges naturally and without preconceptions. If you do not refrain from adorning your emotional response to the object, you end up with superficially decorative language. That is what is known as the spiritual vulgarity of failing to constantly strive for aesthetic authenticity.

In striving after aesthetic authenticity, you must learn from the minds of the people of the past who mastered poetry (fûga); and, closer to our own time, comprehend the mind of our Teacher. If you do not know his mind, there is no means by which you may achieve the Path of authenticity. In order to know his mind, you must track back through the evidence of his writings, and study them well. That is to say, correcting the failings in your own mind, directing yourself towards understanding our Teacher, and working towards achieving insight is what we may call striving for authenticity.

It is poetic egocentrism to not seek the essence of what our Teacher longed for; and to instead find pleasure in his Way according to one’s own biased way of thinking, and feign being one of his disciples. Disciples must sufficiently reflect on and correct their own shortcomings.

Our Teacher’s statement “learn about the pine from observing the pine, learn about the bamboo from observing the bamboo” also was an admonition to separate yourself from egocentrism. This admonition to “learn” refers to the fact that people usually depend on preconceived notions and in the end do not learn by observation. “Learn” means writing your verse after you immerse yourself in exploration of an object so that its particular characteristics appear and stimulate your emotion. No matter what object you write about, if the emotion is not one that emerges from that object spontaneously, object and the self remain separate, and that emotion does not achieve aesthetic authenticity. It remains a creative impulse rooted in egocentrism.

Sunday, September 14, 2014

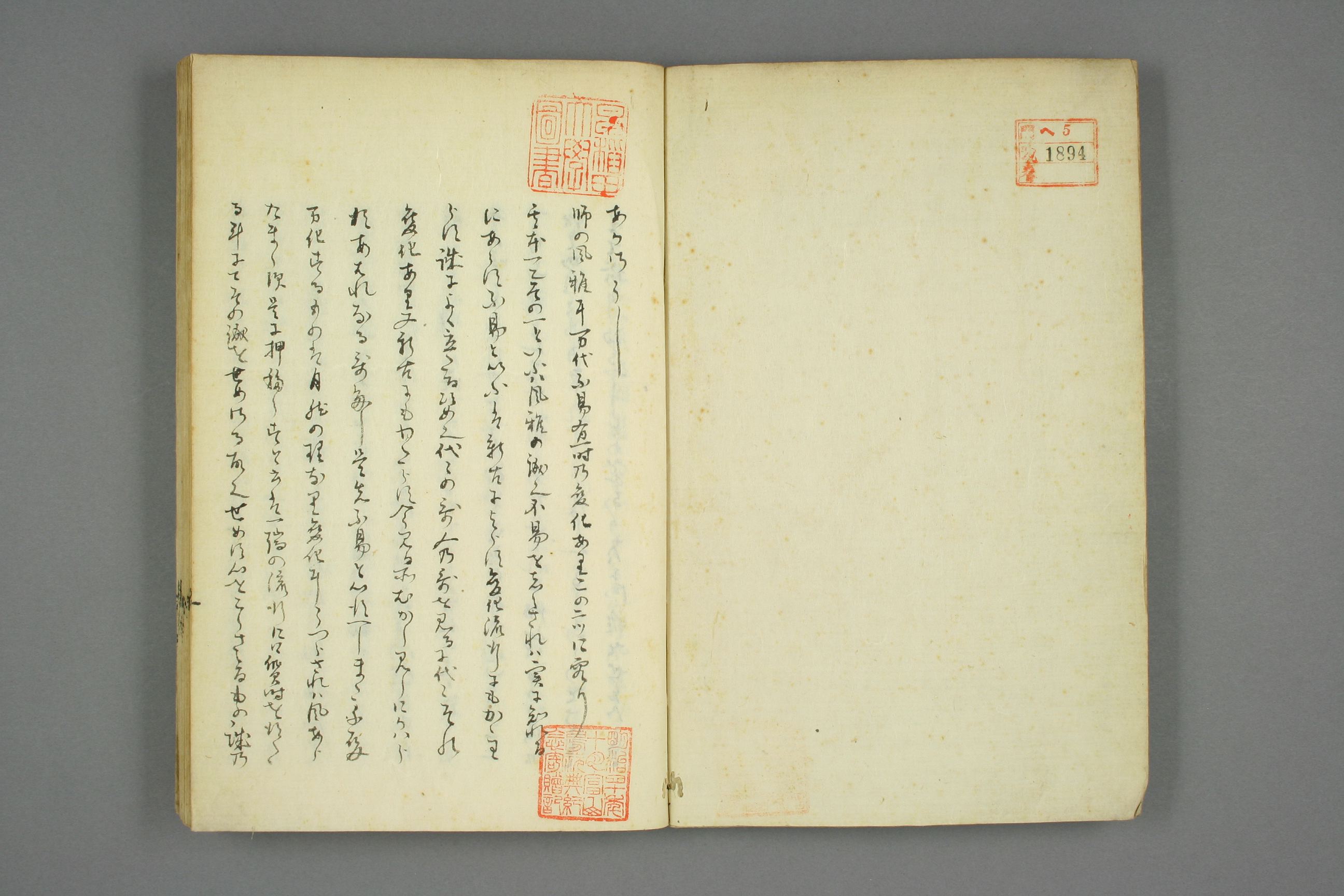

Sanzôshi 3 - The Red Notebook 1 赤冊子

Here's a bit of Dohô's Akazôshi for a cloudy September Sunday. I'm working on this to get ready for a conference at the University of Connecticut in October:

Moreover, transformation is a fundamental principle of Nature. Without change, style stagnates. Style does not change when poets only match their habits of writing to what happens to be fashionable at the time, without singlemindedly striving to achieve aesthetic authenticity. Poets will not understand the aesthetic authenticity of change without singlemindedly striving for and focusing their minds on it. All they can do is imitate others. Poets who strive for aesthetic authenticity find it difficult to be content just with covering the same ground that was previously walked by others; as a rule, haikai style naturally keeps moving forward.

Our Teacher’s haikai (fûga 風雅) possesses both the changelessness of countless aeons and the change of a single moment; looking carefully into each reveals that they both share a single foundation. This single foundation is called the aesthetic of authenticity (fûga no makoto 風雅の誠). If you are ignorant of changelessness, you cannot truly understand haikai. Changelessness means the quality of verse that is established by sincerely seeking aesthetic authenticity that is apart from being either new or old, and is of course not influenced by changeableness or fashions.

If you read the verse of waka poets over the generations, you see that each era had its own changes. There are many waka poems that are evocative regardless of whether they are new or old, or whether their readers are those of the present day or those of the past. It is important to understand this aspect of changelessness.

|

| Akazôshi at Waseda University Library |

Regardless of how many changes there are in the future, the aesthetic authenticity of all change belongs to our Teacher’s haikai. He said, “Do not for a minute swallow the dribblings of the ancients. All things renew themselves like the four seasons progressing forward; haikai is like everything else in this regard.”

When our Teacher was on his deathbed, a disciple asked him about the future of haikai (fûga). Our Teacher said, “There have been numerous stylistic changes since I embarked on this Path. However, we can speak of them overall in terms of three: standard 真, semi-cursive 行, and cursive 草. Of those three, I have not yet achieved mastery of one or two.” Among the light-hearted remarks that he made during his life, something he said many times was, “The rice sack of haikai has only barely been opened.”

Sunday, February 2, 2014

Sanzôshi 2 - The White Notebook 2 白冊子

Here's the second part of the draft.

Lord Fujiwara no Teika said this about haikai. “It is cleverness. It must be something whose emotional content is false. It applies emotional content to something that is without emotional content, and gives expression to what is without expressiveness, in a form that is clever.” In [Ming period poet Pu Yanglai’s 濮陽淶] Yuan-era rime studies compendium (Yuansheng yunxue dacheng 元聲韻學大成) “There was much word play (俳諧 haikai) in the poetic language of Zheng Qi 鄭綮 (d. 899).” “Hai” 俳 means humor; “kai” 諧 means relaxed. In the Tang period, they called humorous verse “haikai.”

There is also the term kokkei 滑稽, humor. The term kokkei was used when Guan Zhong 管仲 (c. 720-645 BCE) went to the State of Chu 楚, his answer to the Chu people was said to be kokkei. In Japan, there is the kokkei humor of Reverend Ikkyû 一休和尚 (1394-1481). Kokkei in this case was evident in the witty responses he made to people, that is to say, cleverness. In Kokinshû, the category haikaika 俳諧歌 was created to classify comic verses. With that as a model, verses that use ordinary language were generally called haikai no renga.

With that, haikai began, and for generations it was only played with as cleverness, and its pioneers remained ignorant of authenticity (makoto 誠). More recently, Baiô 梅翁 of Naniwa [Osaka’s Nishiyama Sôin 西山宗因 1605-1682] became well-known for writing in a free, relaxed style, but he achieved less than half of its potential, and still his reputation for skillfulness rests on his use of word-play.

However, our now deceased teacher Matsuo Bashô took up the path of haikai more than thirty years ago, and was the first to attain haikai’s authenticity (makoto 実). The haikai of our teacher was called by the same name, “haikai,” as was used in the past, but it was not the same haikai as it was in the past; it was the haikai of authenticity. So, although in the past there was a genre called haikai, what was it, since all the years people spent writing it was as useless as the inauthentic verses themselves.

Our teacher said, “We have no predecessors on this Path.” He also said, “If you look closely at the examples of people of the past, you can easily obtain that which you sought. Furthermore, the full range of what I conceive of now will be looked at closely by the people of the future. I fear only the estimation of the people of the future.” He said this repeatedly.

There were many people of the past who had a reputation for poetry written in Chinese and Japanese 詩歌. All of them started from and finished with authenticity (makoto 誠). Our teacher brought authenticity (makoto 誠) to that which was without it, and blazed a trail that will long endure. Authenticity (makoto 誠) lasts the ages, and even Heaven waited long for the strong spirit of the person who brought authenticity to the haikai of our time. What a person our teacher was!

Renga and haikai share the same source. Renga and haikai both have content (kokoro 心) and language (kotoba 詞). While content (kokoro 心) may be the same in both renga and haikai, renga and haikai diverge in terms of language (kotoba 詞). There are many examples from the past that establish this. In the text Haikai Wordless treatise 俳諧無言抄 (Haikai Mugon shô, edited by Sôin, 1674), “Whatever is given voice in words is haikai language 俳言 (haigon). Words that might appear in renga but are pronounced with the Sino-Japanese reading are also haigon. Byôbu (folding screen), kichô (curtain screen) hyôshi (rhythm), richi no chôshi (tuning), rei naranu (irregular), and kochô (butterfly) are of this type. Words that appear once in 1,000-verse sequences, like oni (demon), onna (woman), tatsu (dragon), and tora (tiger), and so on, are haigon. Words that are avoided in renga like sakuragi (cherry tree), tobiume (flying plum tree), kumo no mine (peaks of cloud), kirisame (drizzle), kosame (light rain), kadoide (setting off), urabito (fisher), shidzunome (woman of lowly birth), and so on, appear in Haikai Wordless treatise and transcripts of the teachings of [Satomura] Jôha 里村紹巴 (1525-1602). All words of this kind are haigon.

Friday, January 31, 2014

Sanzôshi 1 - The White Notebook 1 白冊子

I've turned my attention to Sanzôshi (Three notebooks), an important collection related to the poetics of the Bashô school. I'm still working on Taorigiku, but for the time being I'm going to get through some passages to get ready for a karon 歌論 workshop on the West Coast in March. As always, this is a draft, so caveat lector.

Compiled by Hattori Dohô 服部土芳(1657-1730) in 1702.

You can find scans of early copies here at Waseda.

Haikai is Japanese poetry ( 歌 uta). Japanese poetry has existed from the time of the creation of heaven and earth. The great female deity and the great male deity (Izanami and Izanagi) came down from Heaven. First the female deity (divinity of darkness) said:

ananiye ya umaji otoko ni ahinu

“Oh, what a lovely youth I have encountered.”

The male deity (divinity of light) said, “

ananiye ya umaji otome ni ahinu

Oh, what a lovely maiden I have encountered.”

We might very well call this Japanese poetry (uta); what is felt in the heart, and emerges in words, that precisely is Japanese poetry. Thus, we regard this as the beginning of Japanese poetry.

In the age of the gods, the number of mora was not fixed. It became so in the age of humans. It became 31 mora from Susano-wo-no-mikoto. This is the verse that established it:

yakumo tatsu idumo yaegaki tumagome ni yaegaki tsukuru sono yaegaki wo

In Izumo, many layers of clouds arise

to live in seclusion with my wife

I will build a many-layered fence

And live behind that many-layered fence

As it is in the style of the land of Japan, it is called waka 和歌.

Within Japanese poetry (waka) there is renga and there is haikai. As for renga, it was given the name renga from the age of Emperor Shirakawa. Prior to having that name, it was called tsugiuta 継歌 : sequential uta. The number of verses was not fixed. In the time when Yamato Takeru no mikoto went east to subdue the barbarians, he recited this verse at Tsukuba Mountain, in Azuma:

Niibari Tsukuba wo koete iku ya kanenuru

since I crossed Tsukuba of Niibari

how many nights

have passed?

When he did, the fire-lighting youth continued the verse:

kaganabete yo ni wa kokonoyo hi ni wa tooka yo

counting them all:

as for nights, nine nights

as for days, ten days

It is said that this is the origin of renga.

In the time when Narihira was in Ise as an imperial hunter, he had this exchange with Itsukinomiya:

kachibito no wataredo nurenu e ni shi areba

since this is a river

over which a traveler may pass

without getting wet . . . .

mata Ausaka seki wa koenan

I wish that I

may again pass through Ausaka Barrier

He wrote the concluding verse with charcoal from a torch on a wine cup, the story goes.

In the era of Retired Emperor Go-Toba, Priest Zenami 禅阿弥 (Zen’a 善阿?) and Kobayashi 小林 (Hokurin? 北林) compiled the guidebooks containing the rules for avoiding repetitiveness and other linked verse regulations. This is called the “Original Canon” 本式. From this, the standards of renga have arisen. Later, there was the “New Canon” 新式.

Compiled by Hattori Dohô 服部土芳(1657-1730) in 1702.

You can find scans of early copies here at Waseda.

Haikai is Japanese poetry ( 歌 uta). Japanese poetry has existed from the time of the creation of heaven and earth. The great female deity and the great male deity (Izanami and Izanagi) came down from Heaven. First the female deity (divinity of darkness) said:

ananiye ya umaji otoko ni ahinu

“Oh, what a lovely youth I have encountered.”

The male deity (divinity of light) said, “

ananiye ya umaji otome ni ahinu

Oh, what a lovely maiden I have encountered.”

We might very well call this Japanese poetry (uta); what is felt in the heart, and emerges in words, that precisely is Japanese poetry. Thus, we regard this as the beginning of Japanese poetry.

In the age of the gods, the number of mora was not fixed. It became so in the age of humans. It became 31 mora from Susano-wo-no-mikoto. This is the verse that established it:

yakumo tatsu idumo yaegaki tumagome ni yaegaki tsukuru sono yaegaki wo

In Izumo, many layers of clouds arise

to live in seclusion with my wife

I will build a many-layered fence

And live behind that many-layered fence

As it is in the style of the land of Japan, it is called waka 和歌.

Within Japanese poetry (waka) there is renga and there is haikai. As for renga, it was given the name renga from the age of Emperor Shirakawa. Prior to having that name, it was called tsugiuta 継歌 : sequential uta. The number of verses was not fixed. In the time when Yamato Takeru no mikoto went east to subdue the barbarians, he recited this verse at Tsukuba Mountain, in Azuma:

Niibari Tsukuba wo koete iku ya kanenuru

since I crossed Tsukuba of Niibari

how many nights

have passed?

When he did, the fire-lighting youth continued the verse:

kaganabete yo ni wa kokonoyo hi ni wa tooka yo

counting them all:

as for nights, nine nights

as for days, ten days

It is said that this is the origin of renga.

In the time when Narihira was in Ise as an imperial hunter, he had this exchange with Itsukinomiya:

kachibito no wataredo nurenu e ni shi areba

since this is a river

over which a traveler may pass

without getting wet . . . .

mata Ausaka seki wa koenan

I wish that I

may again pass through Ausaka Barrier

He wrote the concluding verse with charcoal from a torch on a wine cup, the story goes.

In the era of Retired Emperor Go-Toba, Priest Zenami 禅阿弥 (Zen’a 善阿?) and Kobayashi 小林 (Hokurin? 北林) compiled the guidebooks containing the rules for avoiding repetitiveness and other linked verse regulations. This is called the “Original Canon” 本式. From this, the standards of renga have arisen. Later, there was the “New Canon” 新式.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)