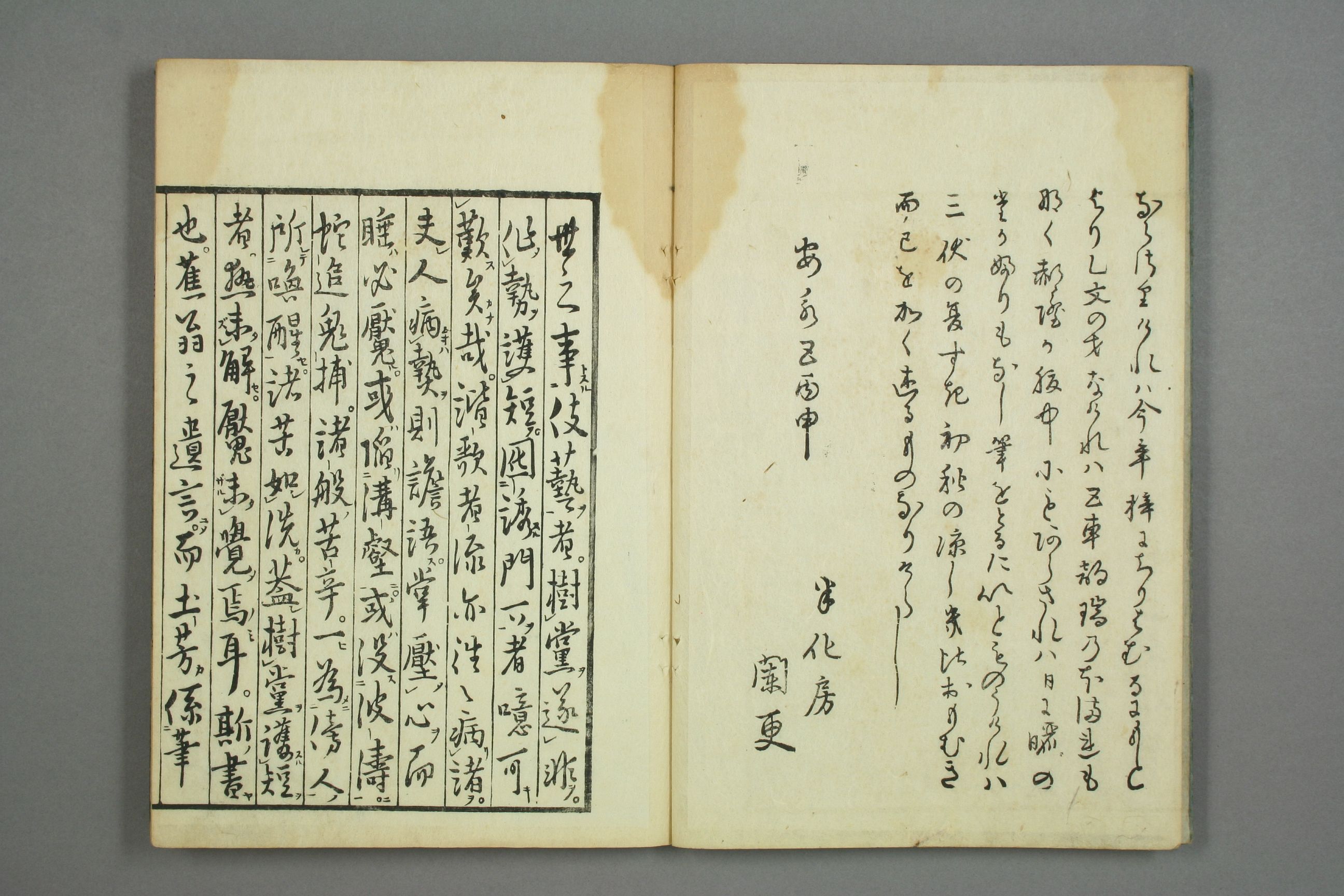

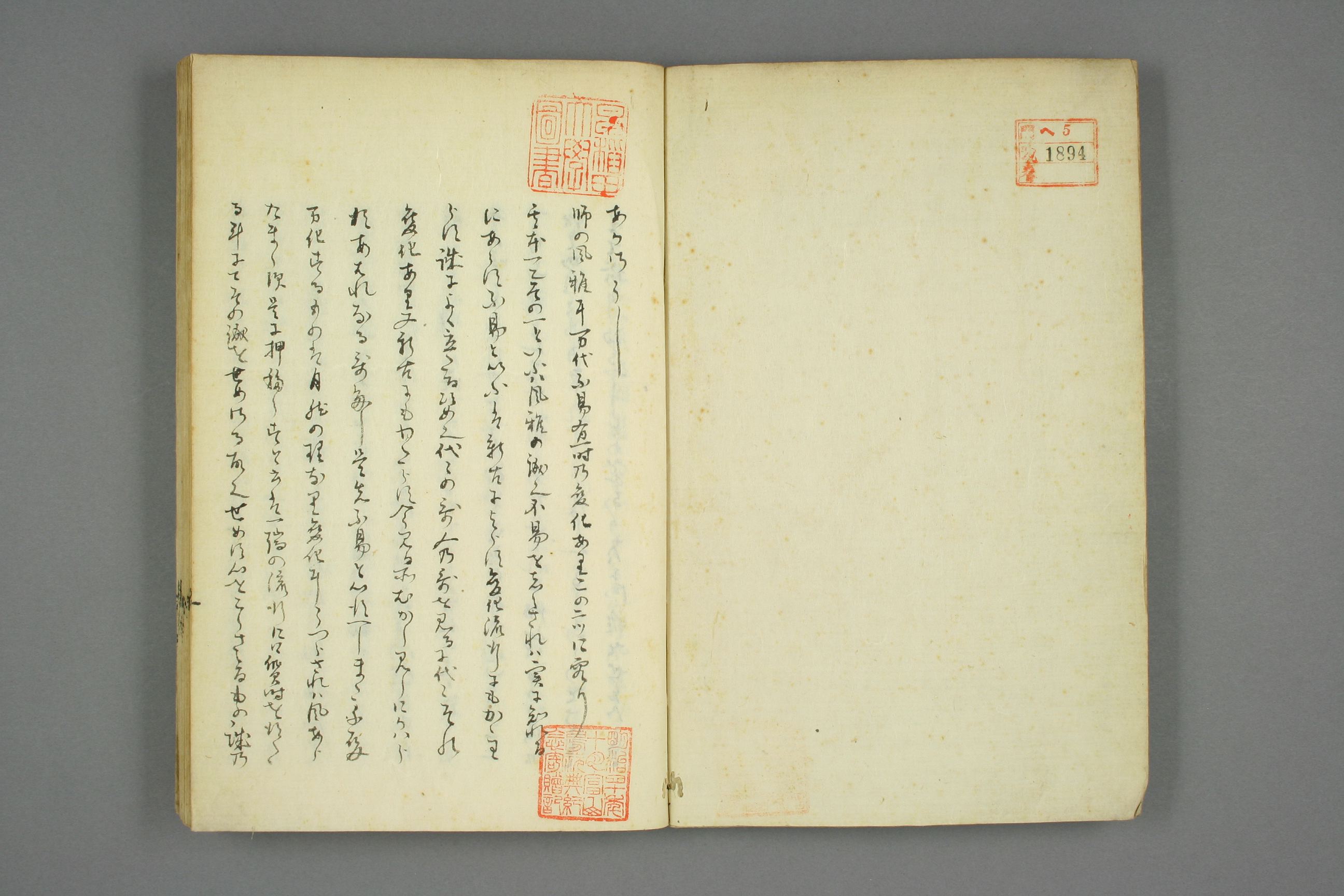

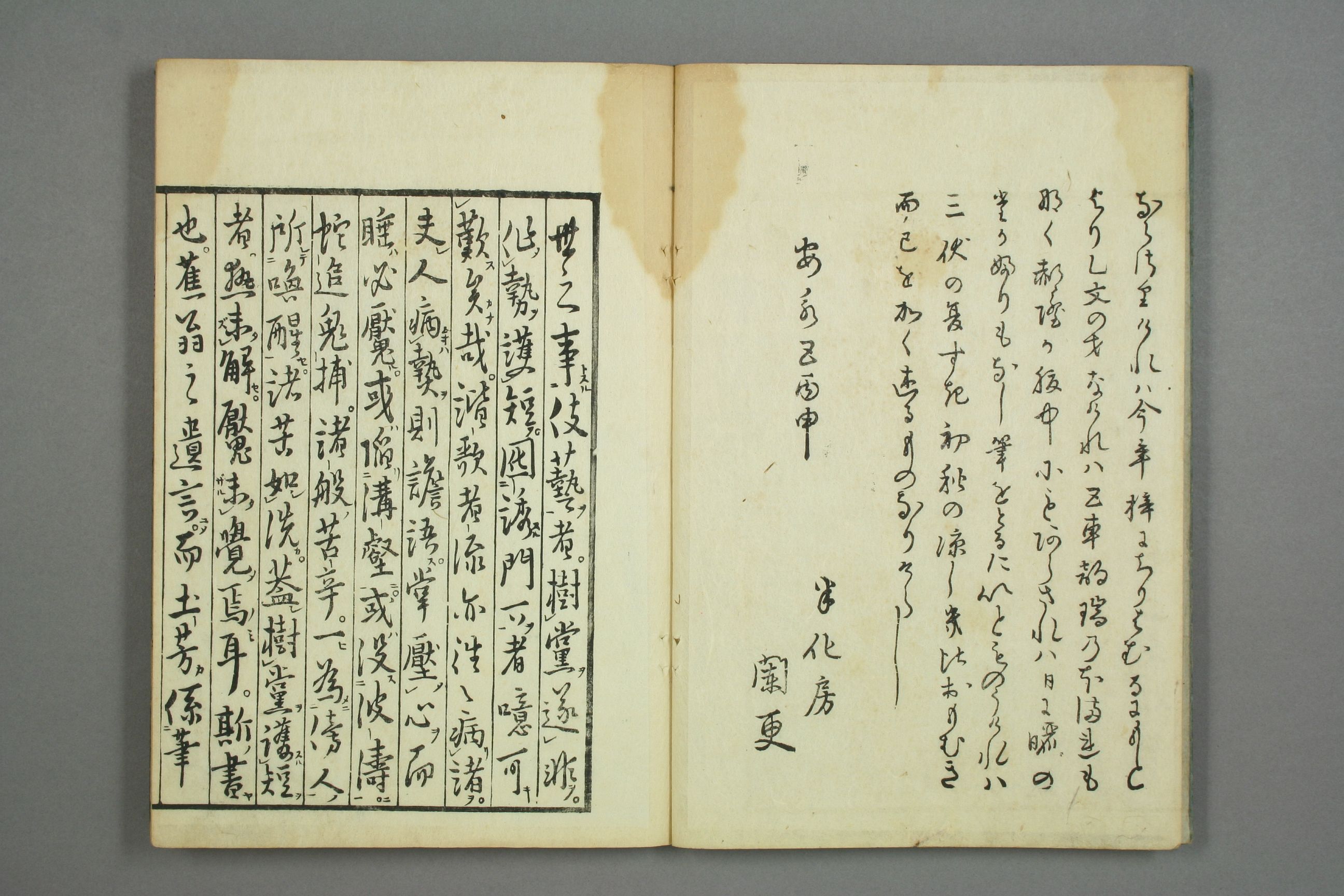

More Akazôshi. This part includes some of Bashô's famous statements on the balance of high and low culture in haikai, and the importance of objective observation.

|

| Sanzôshi, Waseda Library |

One of his teachings was, “Awaken to the things of elite culture, but return to the things of the everyday life.” He said, “Always strive to awaken to aesthetic authenticity; at the same time, you must return to the haikai of the present moment.”

Because poets who always concentrate on poetic elegance unify the object about which they write with the emotion that they feel and fix it in the form of a verse, the theme they take up emerges naturally and without preconceptions. If you do not refrain from adorning your emotional response to the object, you end up with superficially decorative language. That is what is known as the spiritual vulgarity of failing to constantly strive for aesthetic authenticity.

In striving after aesthetic authenticity, you must learn from the minds of the people of the past who mastered poetry (fûga); and, closer to our own time, comprehend the mind of our Teacher. If you do not know his mind, there is no means by which you may achieve the Path of authenticity. In order to know his mind, you must track back through the evidence of his writings, and study them well. That is to say, correcting the failings in your own mind, directing yourself towards understanding our Teacher, and working towards achieving insight is what we may call striving for authenticity.

It is poetic egocentrism to not seek the essence of what our Teacher longed for; and to instead find pleasure in his Way according to one’s own biased way of thinking, and feign being one of his disciples. Disciples must sufficiently reflect on and correct their own shortcomings.

Our Teacher’s statement “learn about the pine from observing the pine, learn about the bamboo from observing the bamboo” also was an admonition to separate yourself from egocentrism. This admonition to “learn” refers to the fact that people usually depend on preconceived notions and in the end do not learn by observation. “Learn” means writing your verse after you immerse yourself in exploration of an object so that its particular characteristics appear and stimulate your emotion. No matter what object you write about, if the emotion is not one that emerges from that object spontaneously, object and the self remain separate, and that emotion does not achieve aesthetic authenticity. It remains a creative impulse rooted in egocentrism.